I collect Haggadahs. I love them; I think the Haggadah is the quintessential Jewish religious text. Not only because it tells the story of how we became a people, but also because there are Haggadot customized for every Jewish family and community. That’s why there are so many hundreds of them out there.

Pride of place in my Haggadah collection goes not to rare volumes or collector’s editions. Instead, I prefer photocopied and homemade texts that families have shared with me over the years, taking the traditional order, texts, and rituals and making the story their own. After all, personalizing the story is the key injunction of this festival: “In every generation, we must view ourselves as if we, personally, came out of Egypt” (Mishnah, Pesachim 10:5). We write ourselves into the continually unfolding story, respectfully inscribing the latest chapter that builds on what came before.

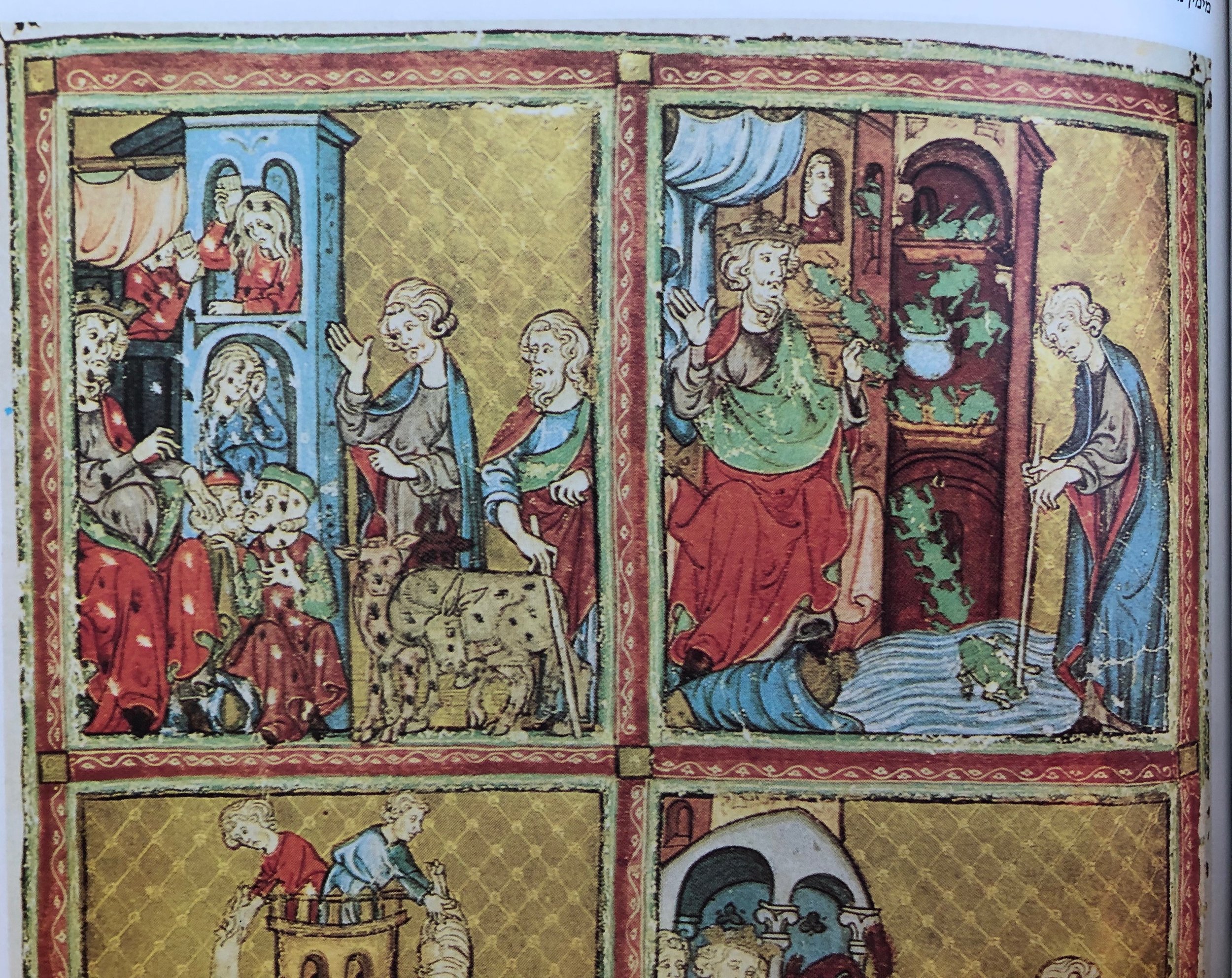

At the culmination of the Maggid section of the Haggadah—the part that tells the story of the Exodus—is a description of the עשר מכות/Esser Makkot, known colloquially as the Ten Plagues. And judging by the Haggadot in my collection, as well as all the creative seder material that fills my inbox at this time of the year, we’ve been doing it all wrong.

Racism. Climate change. Islamophobia… Countless Haggadot and seder-leaders over the years have invited guests to list “10 modern plagues” that afflict our world.

Homophobia. Rape culture. Surging antisemitism… there is no shortage of plagues in our world, and we’re often called by well-meaning people today to elaborate on them at the seder.

Family-separation policies for immigrants. The ubiquity of screens. Allowing rich people to set our communal agenda. Suburban complacency… I can do it, too. I’m sure you have your own list.

But if we think about it, these lists really don’t work at this part of the seder. It’s not that these things aren’t important—they are, and each contributes to a form of “enslavement” that we all yearn to be free from.

The problem is, that’s not what the מכות עשר / Esser Makkot / “Ten Plagues” are all about.

Makkot are not “plagues.” They are “strikes”, as in military strikes against an aggressive enemy. That is precisely the image that the Torah presents in the Exodus story: G-d is waging a battle against Pharaoh in order to achieve the liberation of the Israelite slaves. At the burning bush, G-d tells Moses:

וְשָׁלַחְתִּ֤י אֶת־יָדִי֙ וְהִכֵּיתִ֣י אֶת־מִצְרַ֔יִם בְּכֹל֙ נִפְלְאֹתַ֔י אֲשֶׁ֥ר אֶֽעֱשֶׂ֖ה בְּקִרְבּ֑וֹ

וְאַחֲרֵי־כֵ֖ן יְשַׁלַּ֥ח אֶתְכֶֽם׃

I will stretch out My hand and strike [v’hikeiti – the same root as makkot] Egypt with

various wonders which I will work upon them; after that he shall let you go.

(Exodus 3:20)

This process unfolds over a series of 10 strikes against Egypt, each one a tool towards bringing about freedom: blood, frogs, lice, etc…

When the Torah recalls the Exodus, it refers to these events as “signs” and “wonders”. In Deuteronomy 34:11, they are called אותות (“signs”) and מופתים (“portents”); these words are used again in Psalms 78 and 105. They are divinely attributed miracles that directly brought about the release of the people from bondage.

The “Ten Plagues” are the tools of liberation. They are not lingering calamities from which the world suffers, like racism, environmental cataclysm, or ignorance. They are not called “plagues.”

The Torah has words for “plague”: נגע / nega’ and מגפה / magefah. Nega’ usually appears in the context of leprosy, the scale-disease that was a particularly horrible trauma in the Bible. (Later, a whole tractate of the Mishna on this theme would be called Nega’im.) Magefah is used usually in the context of massive deaths after the Israelites sin as a community (see, for example, Numbers 14:7, 25:8-9, 26:1; and 1 Samuel 4:17). But neither term, nega’ nor magefah, conjures up God’s battle with Pharaoh.

There is one exception (because there’s always an exception). In Exodus 11:1, just prior to the מכת הבכורות / the strike against the first-born of Egypt, G-d tells Moses:

…ע֣וֹד נֶ֤גַע אֶחָד֙ אָבִ֤יא עַל־פַּרְעֹה֙ וְעַל־מִצְרַ֔יִם…

“I will bring but one more plague [nega’] upon Pharaoh and upon Egypt…”

Here is the one appearance of the word “plague” in the entire saga. Why does this word appear here, and only here?

Perhaps that Tenth Strike is different. After all, scholars have pointed out that the Esser Makkot occurred in three triads; there is a literary symmetry in the clusters of three, and the Tenth stands outside of the pattern. Perhaps the severity of the 10th Strike is so intense that even G-d realizes that this is the “nuclear option.” Maybe it’s simply the exception that proves the rule, since nowhere else in biblical or rabbinical literature these events are called “plagues.”

So it’s just a little too lazy to score political points by asking, “What are 10 modern plagues…?” We have more than our share of them, it is true. But there is a cognitive dissonance in linking the today’s blights with wondrous moments in the past that directly led to our freedom.

The seder saga inspires other, more appropriate and difficult questions: What “miraculous” things have contributed to our freedom – individually, as a family, and as a people? What wondrous events in our past directly made it possible for us to be here today? And how do we appropriately express our wonder, awe, and gratitude?